Understanding self-care

Self-care is an important part of everyday life for us all. We each take care of ourselves as best we can in our daily activities, to maintain personal health and happiness, whilst also functioning at an optimal level in our professional endeavours.

But self-care is more than you think, and it becomes even more important when we are faced with personal challenges or occupational stress. For people involved with palliative care, emotional distress, compassion fatigue and burnout are important considerations. 1-5

Effective self-care strategies are vital to coping with stress and building resilience.6 The importance of self-care and staff support is reflected in Palliative Care Australia’s National Palliative Care Standards, which highlight self-care as a shared responsibility.7

Unfortunately, there can be a stigma around self-care that suggests it is somehow selfish to look after yourself if you are caring for others. However, the care we offer to others depends on our own self-care and wellbeing; 8 indeed, the ‘Total Care’ for patients discussed by Dame Cicely Saunders can also include the people providing care.4

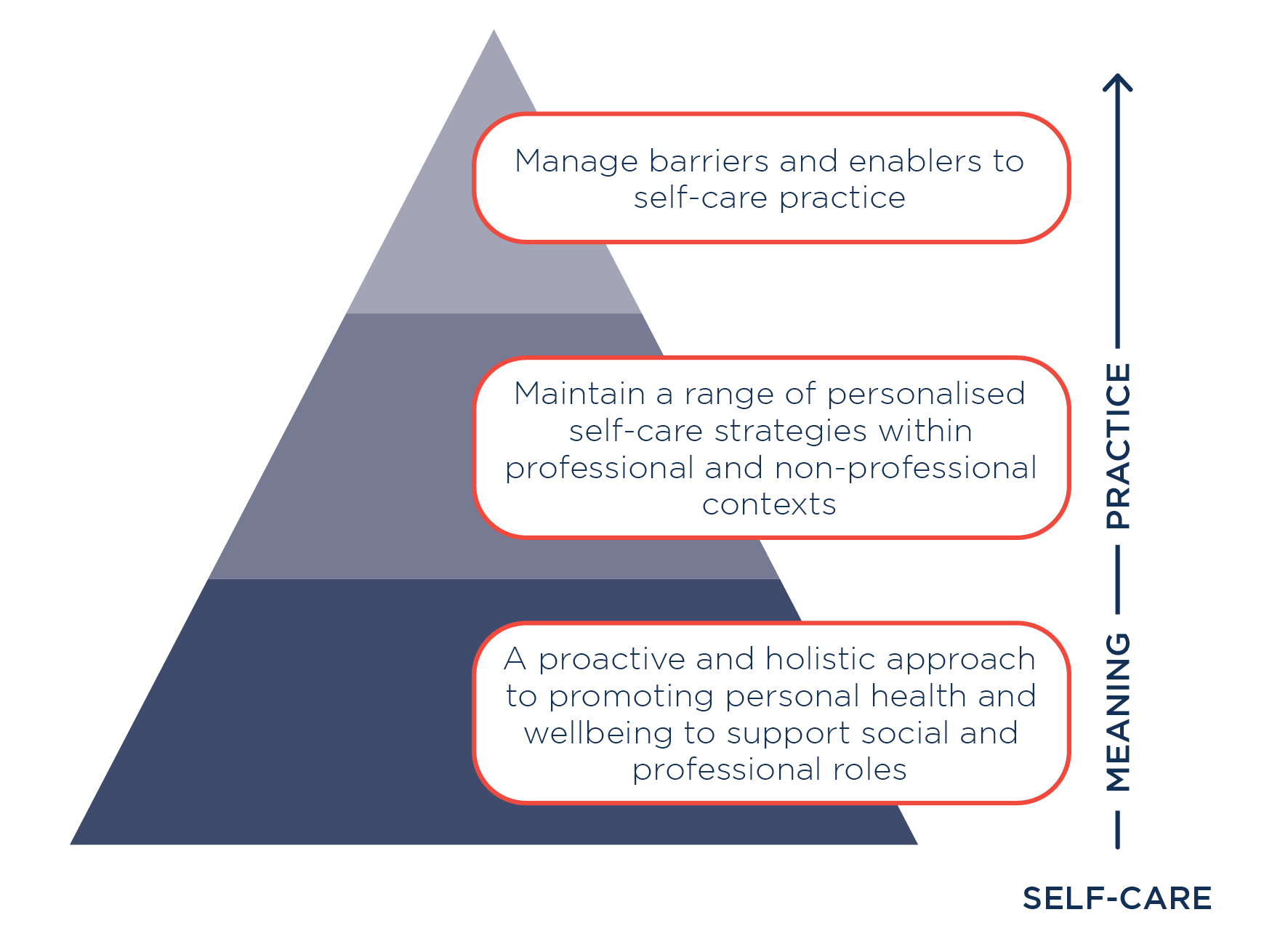

‘Self-care’ can mean different things to different people. It’s an individual thing. But there’s a common thread spun across a diverse range of thought and understanding. A national study of palliative care nurses and doctors in Australia9 found that self-care is ‘a proactive and holistic approach to promoting personal health and wellbeing to support social and professional roles.’

The same study identified that effective self-care involved maintaining a range of personalised self-care strategies within both professional and non-professional contexts. Importantly, it is essential to manage barriers and enablers to self-care practice.

When self-care is properly understood, it is prioritised.10 In the same way that the human heart must first pump blood to itself, a person must take care of their own health and wellbeing to sustain their capacity to serve and/or care for others.11

Return to Self-Care Matters to learn more about planning for self-care.

References

- Martins Pereira S, Fonseca A, Carvalho A. ‘Burnout in palliative care: A systematic review.’

Nursing Ethics. 2011. 18. 317-326. - Portoghese, I., Galletta, M., Larkin, P. et al. ‘Compassion fatigue, watching patients suffering and emotional display rules among hospice professionals: a daily diary study.’ BMC Palliative Care. 2020. 19;

- Cross LA. ‘Compassion fatigue in palliative care nursing: A concept analysis.’ Journal of Hospice & Palliative Nursing. 2019. 21(1); 21-28.

- Beng, Tan Seng, et al. ‘The experiences of stress of palliative care providers in Malaysia: A thematic analysis.’ American Journal of Hospice and Palliative Medicine. 2015. 32(1); 15–28.

- Dein S, Abbas SQ. ‘The stresses of volunteering in a hospice: A qualitative study.’ Palliative Medicine. 2005. 19(1); 58-64.

- Alkema K, Linton JM, Davies R. ‘A study of the relationship between self-care, compassion satisfaction, compassion fatigue, and burnout among hospice professionals.’ Journal of Social Work in End-of-Life & Palliative Care. 2008. 4(2); 101-119.

- Palliative Care Australia. ‘National Palliative Care Standards’ 5th Edition. 2018. PCA: Canberra ACT. https://palliativecare.org.au/standards

- Mills J. ‘Self-care, self-compassion and compassion for others.’ 2018. The University of Sydney.

- Mills J, Wand T, Fraser, JA. ‘Exploring the meaning and practice of self-care among palliative care nurses and doctors: A qualitative study.’ BMC Palliative Care. 2018. 17; 63.

- Mills J, Wand T, Fraser, JA. ‘Palliative care professionals' care and compassion for self and others: A narrative review.’ International Journal of Palliative Nursing. 2017. 23(5); 219-229.

- Mills J, Wand T, Fraser, JA. ’On self-compassion and self-care in nursing: Selfish or essential for compassionate care?’ International Journal of Nursing Studies. 2015. 52(4); 791-793.