Spiritual care at the end of life; how to reduce distress as we face dying

Spiritual care at the end of life; how to reduce distress as we face dying

by Heather Wiseman

Tuesday, December 06, 2016

There is a form of suffering at the end of life that has nothing to do with physical pain. Existential or spiritual pain can cause great distress, which is why psychological, social and spiritual care is such an important part of palliative care. So how does spiritual care differ from pastoral care and what issues tend to distress us in our dying days? Palliative Matters asks Andrew Allsop, psychosocial and spiritual service support manager for Silver Chain and a Palliative Care Australia Board member.

Having cared for many people as they face the reality of their own death, Andrew Allsop has heard first-hand many issues that can cause significant spiritual distress. Generally, spiritual distress is related to the dying person’s life story; their connections to people and places and the events and experiences that have given their life meaning and purpose.

Mr Allsop, who manages psychological and spiritual support for Silver Chain, says the concept of spiritual care is often confused with religion. While for some people the two concepts overlap, for others there is a significant distinction.

“Religion is for many people one of the ways they might conceptualise and experience their spirituality. For some people, religion might define their spirituality completely, whereas for a lot of people it may be just a component. For many more, religion may have no place in their spiritual world view at all.

“When we are looking to understand a person’s spirituality, we are looking at all the things that give meaning and purpose to a person’s life. Spiritual care is about trying to develop an understanding of the issues that are significant to a person.

“If they’re experiencing significant spiritual or existential distress, then it is then trying to get a sense of what is leading to that. They may be feeling incredibly isolated, totally disconnected, demoralised and have a sense of hopelessness, because they are struggling to really come to terms with what their life has been about. They may need support as they grapple with what has given their life meaning and what will sustain the life they have left.”

Mr Allsop says providing spiritual care requires being fully present to what the dying person is experiencing, rather than minimising it, distracting from it, or looking for a cure.

“Nothing is going to solve it. It’s not about trying to fix something. It’s actually being present to that person’s feelings, pain or grief, whatever that might be. It’s then trying to help people develop a sense of meaning where they feel there hasn’t been any, or there isn’t any.”

Mr Allsop says there is mounting international evidence that tailored spiritual care can improve general health outcomes. However, palliative care is one of the few specialties which recognises the importance of spiritual care.

While spiritual care workers may have particular skills in engaging with people on issues of spiritual significance, it is important for all health professionals to have a sense of how important spirituality is for their patients, and for themselves.

“How we frame it is unique to each of us,” says Mr Allsop.

“It’s about listening and validating the life that a person has led.”

Below, Mr Allsop explains just a few of the many issues that affect people’s sense of spiritual wellbeing at the end of life.

Religion and issues of faith

Mr Allsop says some people find their religion a great source of comfort, inspiration, hope and peace in the lead up to death. But this isn’t always the case.

“Religion may assist them very profoundly in how they view what is happening to them and facing up to the immediacy of the end of their life,” he says.

This is particularly true of people who believe there is something better to look forward to.

“But having a strong faith tradition doesn’t necessarily guarantee that people will not experience a level of distress.”

For some people, religion actively contributes to their distress and makes them fear dying, particularly if they believe in a punishing god.

“Other people may become extremely angry and upset, questioning what they have done to cause this and why it is happening, and asking ‘How could a caring, loving god do this to me?’

“Then they really go through that crisis of faith and that may leave them feeling angry and totally empty in terms of having nothing to hold on to.”

Mr Allsop says when religion is the source of great distress, some people benefit from connecting with someone who shares a deep understanding of their faith. A priest or minister may be able to interpret a distressed person’s world view and counter any misunderstandings that may be causing grief.

Rituals associated with forgiveness can have a profound impact on someone who is deeply troubled by the things they have done.

Connection with people and place

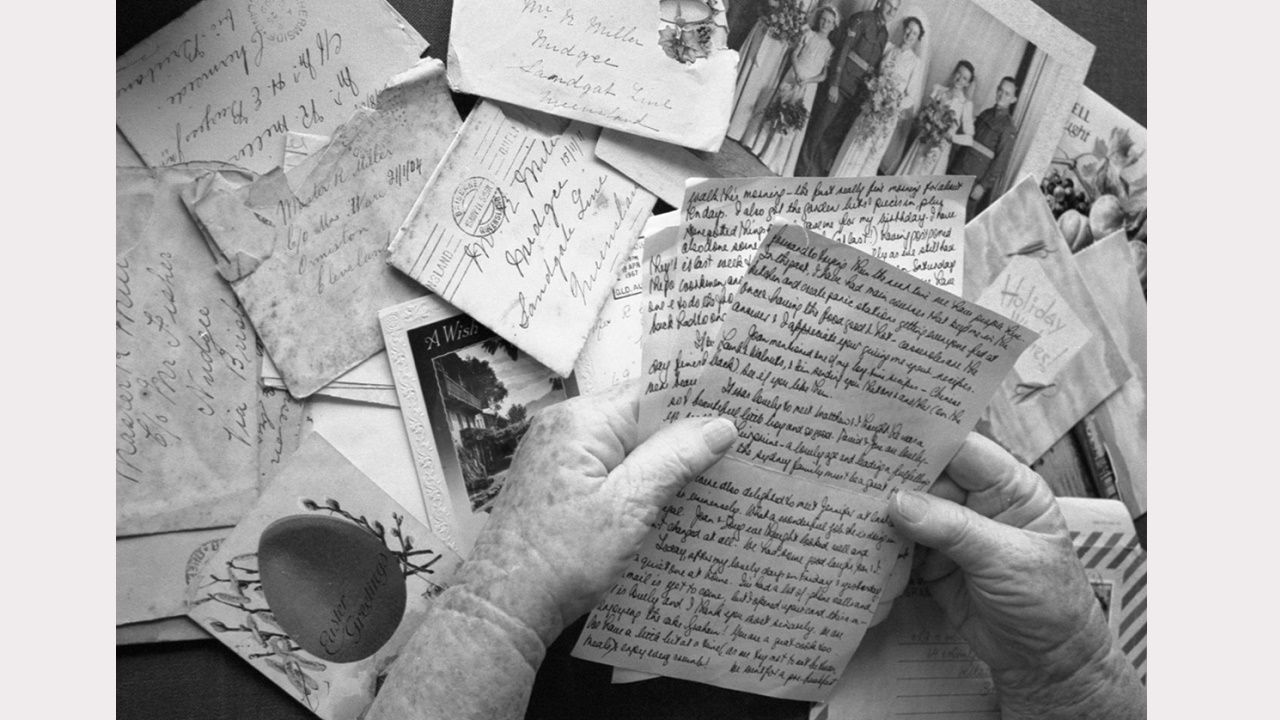

Mr Allsop has worked with many dying people who derive enormous joy and meaning from their connections with others, their community and activities they enjoy.

“So some people who are walkers or hikers derive their meaning and spiritual peace from that. It is important to be able to understand that and facilitate those connections, so people don’t become disconnected and isolated from the experience, and it can continue to give their life meaning.”

They may not be well enough to hike, but they may enjoy being outside in the fresh air, telling stories about past hikes, or looking at photographs of their previous adventures.

Connections with home and other places, such as a place of birth, are important to many people, which Mr Allsop says can inspire an intense desire to die at home.

“Rather than dying in a hospital, many people want to be in a familiar environment. That is where memories and meanings have accumulated over their lifetime and being at home is where they can make those connections best.

“For many cultural groups, connection to place has a very spiritual meaning. That’s particularly true for Aboriginal people, who may want to return to country or remain on country when they die.”

A life well lived

It’s natural for people dying an expected death to look back over their life and consider what they have achieved. Should they decide they haven’t achieved much, or have deep regrets, their poor sense of worth can lead to significant suffering.

Mr Allsop says feelings of hopelessness and emptiness can leave people agitated, distressed and not at peace. Some will feel and remain angry, if they’re not able to reconcile their life’s achievements.

Generally however, there is value in exploring what has given people meaning and purpose, thorough discussions that don’t focus on success measures that are relevant to others.

“We help them reorient themselves to recognising that they’ve added value through raising a family or their relationships with their children. Sometimes they’ve been using measures of success to do with status, work, or finances and so they feel they could have accomplished a lot more.

“But through a process that allows them to reflect on what they have done with the people closest to them and who their loved, they realise their greatest legacy is what they did with their family. That brings great comfort to them and that change can be really powerful.”

Like minds and shared experiences

Some people have defining experiences in life, which may have occurred decades ago and occurred over a relatively short time. Those experiences may become more significant as people review their lives and who they have become.

Mr Allsop says this is particularly true of people who have gone to war. He has seen instances where veterans’ anger and frustration intensifies at the end of life. This significantly impacts on their partners, who struggle with not being able to connect with their silent, remote and disconnected loved one.

“The trauma the veterans experienced happened a long time ago, but because they are dying, this is amplified. To have someone who can come in and connect with their experience is profound and can have a significant impact.”

He admires a colleague’s ability to connect with war veterans. Having served as a navy chaplain and Anglican priest, he can speak their language and has a “one of the mates” approach.

His colleague taps in to a sense of comradery, which many veterans value, and is comfortable with silence.

“He does some really great work with people who have been quite significantly damaged by their experiences,” says Mr Allsop.

“He is there as a very genuine person, not to impose anything, but to listen. Because of his own experiences, he is really able to connect in a spiritual way.”