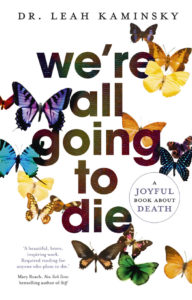

GP tackles her fear of death

Melbourne GP and writer, Dr Leah Kaminsky, kicks off her latest book with frank acknowledgement that she has always had a profound fear of death.

It’s an admission that is a great leveller, reminding us that even doctors – with the great advantage of all their clinical knowledge and experience – aren’t necessarily ahead of the rest of us mere mortals when it comes to quietly accepting that “We’re all going to die”.

That is the title of Dr Kaminsky’s new chatty, easy-read, which invites you to take a seat in her consulting room and learn – as she has – from her patients.

Dr Kaminsky admits that she’s always preferred the lighter side of medicine. She has never enjoyed breaking bad news (“I’ve always been more of a birth kind of person; it might be oozy and painful, but at least you get smiles and champagne all round at the end”). She’s the kind of doctor whose gut churns and internal shutters close when she scans through a patient’s test results and discovers they have a death sentence.

But after the death of a friend, Dr Kaminsky realised that “being a doctor who was terrified about death was like a pizza chef with a phobia about dough”. She got stuck into exploring her fear, with an honesty, humility and openness that makes for an engaging read.

She shares publicly for the first time the story of her mother’s death and the complex feelings of shame it once caused her; the trauma of having a six-year-old boy admonish her for not being honest about pain before sticking a needle into his spine; and how 30 years ago as “clueless intern, fresh out of medical school” she was accused of attempting to euthanise a little old lady after upping her morphine dose to relieve her pain.

“I do not want heroics and I do not want to suffer."

“I hesitated to put so much personal stuff in, but it needed to be there,” she tells Palliative Matters, suggesting that anything less would have been disingenuous.

“I almost wrote the book to find out what I think and I use myself as a guinea pig publicly.

“I don’t have answers; I feel like the dummy at the back of the class. But in writing this book, it was more important for me to ask the questions and generate public discussion.”

In parts, the book is confronting, and far from reassuring. She writes, “I have seen so many bad deaths in my years working as a doctor that I wonder whether the notion of a good death is something truly achievable for most of us.”

But ultimately that is the raw base of Dr Kaminsky’s fear. She’s not scared of the prospect of being dead. It’s a fear of not being able to control death’s trajectory and being forced to undergo unnecessary medical procedures.

“I’ve seen to many people who – even though they’ve stated they don’t want to -- have had to go through medical heroics at the end of life. I have worked in hospitals where we have pretty much resuscitated dead people.

“I do not want heroics and I do not want to suffer. I don’t want the treatment to be worse than the condition and I’d rather live a shorter, richer life than prolong my life at all costs. If my quality of life is going to be shocking, I don’t want to put my family through that.

“We still have this focus on saving lives at all costs and yet all the dying people cluttering up [intensive care] wards should be given the dignity of a peaceful death. I’ve had patients at the end of their lives who’ve had medical professionals say let’s have another round of chemo. Let’s not give up hope. I don’t know how to stop it, but it needs to be shaken out and discussed in public forums.”

She says there needs to be a revolution, which brings death back into discussions that occur in the public arena, in the same way that society has become accepting of conversations about sex.

“Death is hidden away and we don’t talk about it. It’s off the stage of life. I wanted to bring it back on stage. My premise is that if we can have fruitful and open discussion about death and the process of dying, and what our options are, it brings our life into focus and it gives us more control as human beings over the trajectory of our lifecycle.”

She says writing the book was like going on a road trip into the world of death and dying, but it was fun in many ways. It has made her a lot more willing to talk about death, which has built deeper relationships with patients.

“In a professional sense, if I can’t talk to my patients about death, and bring it up in a sensitive way, I don’t think I’m doing my job properly. When you have those difficult conversations I think people are genuinely relieved -- they want to have them. You forge a bond.”

On a personal level, writing the book has left Dr Kaminsky grateful to be alive, and more conscious of that gift every day. She says she is less likely to worry about things that are trivial stuff or focus too hard on things she “should” do. Instead, she is revelling in trying to make a difference.